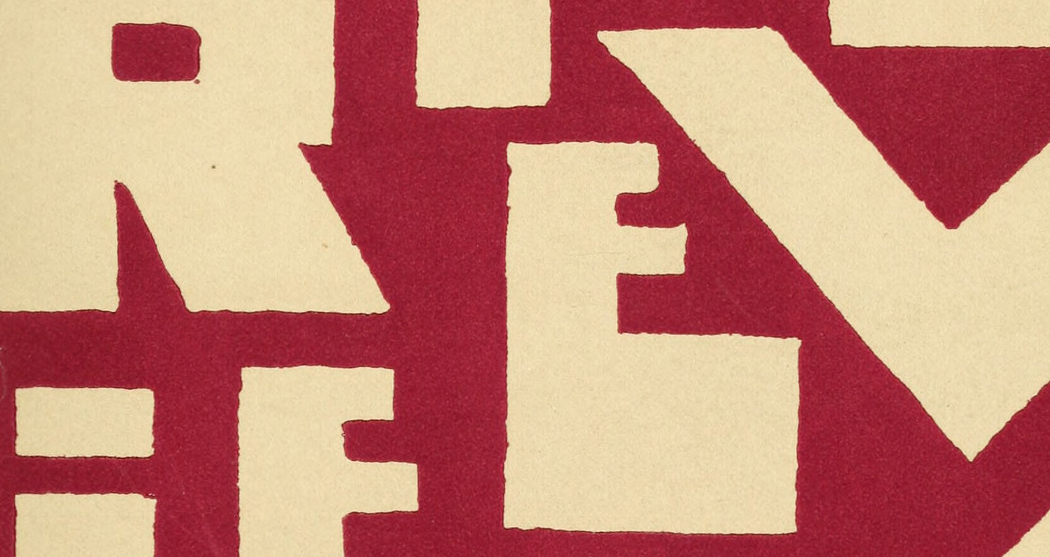

A insight into Vorticism in Blast's art piece," March" by Edward Wadsworth.

Submitted by Drake Duis on Thu, 09/16/2021 - 01:59In the modernist journal, Blast, No. 1. A piece titled," March" by Edward Wadsworth, shows a array of abstract curved objects in what appears to be a dark place, with a small crack of light illuminating the otherwise dark place. It almost looks as though the objects are alive in some ways as they curve and distort. It gives the feeling that the objects in the piece are almost trying to reach for the light even if they are unfamiliar with what they are experiencing. This has distinct ties with Vorticism as it displays these harsh, ragged pieces of machinery that got displayed by some light source off page.

This piece gives an overwhelming feeling of something being cast away and finally being revealed, even for a moment. This seems to tie with the movement of Vorticism as it was a modernist British movement that focused on displaying the culture and spirit of that era through this rough mechanical content. In the Industrial Revolution, it would make sense that people of that time would feel like those warped mechanical pieces that are craving for the chance to be revealed even if only dimly. There is something to say about how these art pieces seem to show so little, but reveal so much at the same time. "March" seems to be a intriguing piece about the time that it took place in the movement of Vorticism.